Aligning the human solution with the computer

In the two sessions so far we have covered the four pillars of computational thinking:

- algorithms

- decomposition

- pattern recognition

- abstraction

These approaches have allowed us to develop a solution to our problem. Critically at this stage it is likely that the solution still looks like a human solution. In this lesson we are going to think about how we translate this solution into something we can write code for. To do this we need to align this human solution to concepts, constructs or paradigms for our language of choice. Whilst computational thinking is agnostic of programming language, this translation element may vary depending on the specific language. There are however some common themes we can identify.

If you have the knowledge of a couple of different languages, with your solution in hand you are now in a position to evaluate which of those might be the best fit. Computational thinking and separating the design of the solution from the actual coding has benefits for even more experienced practitioners.

The foundational blocks of most programming languages are objects and functions. Objects are the basis of variables you define or declare. Functions are processes or actions you perform (often to objects but not always). When we talk about aligning our human solution to one a computer understands, we need to reframe it in terms of variables and functions (or the processes underlying those functions).

The most relevant approach here is abstraction. We need to identify which information our program needs to know in order progress through the workflow.

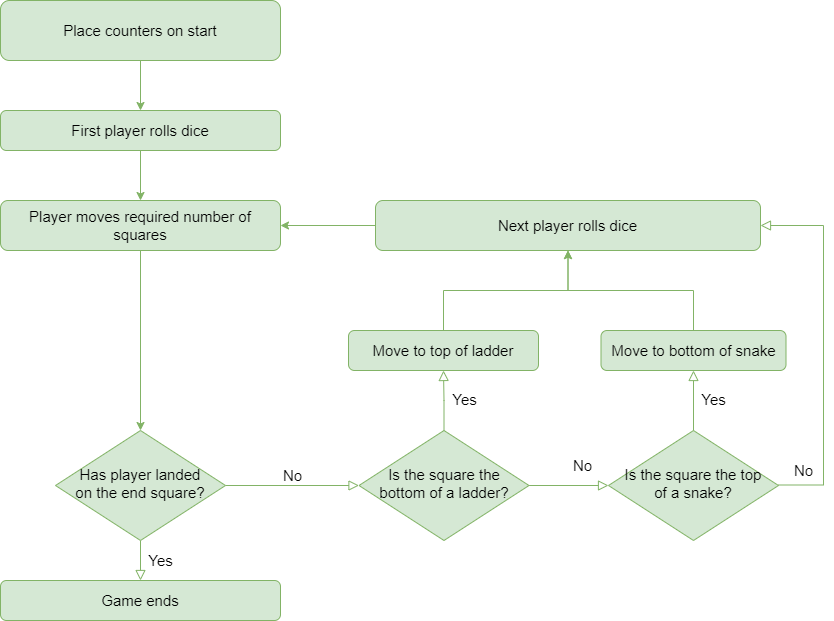

Let’s return to our snakes and ladders example. Here is a flowchart of the human solution.

Th crux of the game is the movement around the board. At any point in time the computer needs to know where each player is located. Using abstraction, the critical piece of information is then the number of the square that the player is on at that time in the game. We need a variable to store this for each player. We could have a series of variables (“P1”, “P2”, “P3”, …) but snakes and ladders does not have a fixed number of players. It could be between 2 and 4. So it could be that some of these variables become redundant or we don’t declare enough of them.

This highlights that another critical piece of information for our program is the number of players. With this information we can create a list or vector or array of the required length to hold the positions of all players. We will call this P.

To start the game, all players move to the first square, so all elements of P need to be initialized to 1.

The players will take it in turns to complete their go. In order for this rotation to occur the program needs to know which player is currently taking a turn. We can organise P such that the elements are ordered by the order of turns. This makes it easy to keep track. We will need a variable though to denote which player is currently playing, we will call this i. We can easily move to the next player by increasing the value of i by 1, unless i is the maximum number of players in which case it returns to 1.

We then start rolling the dice. To know where the current player is going to move to, we need to know the value of the dice roll, so this becomes another variable. We will call this D. We only need one element here as the players only roll the dice one at a time. Once the dice has been rolled we add this value to the current position of the current player. We can use i to extract the current position (by slicing or subsetting) and then replace it with the new position.

Before this player’s go is over, we need to check whether they have landed on either a snake or a ladder to determine if they need to move again. We are using this information to make a decision, we need to introduce two pathways in our program based on a criteria. This can only be achieved with an IF statement. To use an IF statement we need a condition we can evaluate to be either TRUE or FALSE. Furthermore, there are multiple possible squares with either snakes or ladders we want to check we have not landed on. We need a reference list of squares with snakes heads or bottoms of ladders to check. What’s more, if we are on either a snake or ladder we will then need to know which square we are sent back to or advanced. In python we could use a dictionary where the key is the head of the snake and the value the tail, in R we would probably use a data.frame. If TRUE, we then replace the current position with the end of the snake or ladder (the value we looked up in the dictionary).

This is a completed go and play now passes through to the next player. So we have already discussed how our variable i is used to track the progress of the game. But how do we get our program to rerun the same process for each player? Our flowchart clearly shows the repetition element of the game, and as we are iterating through players we might think that we need a for loop. However, a for loop will only rotate through each player once. It will then stop.

It is unlikely the game will be finished after one turn. If we knew how many turns would be needed we could do a nested for loop to loop through the players a set number of times or a single for loop to process a set number of turns, but we don’t know what the total number of gos or turns will be. We could set it to loop a conservative number of times, such that the game is guaranteed to finish before that expires. This might work but isn’t a great solution. Firstly, there is an element of guesswork, what would an appropriate number be? Secondly, this wouldn’t scale (if we were to increase the number of squares on the board for example). Thirdly, we would need to add into our loop an IF statement to check if the end criteria has been met so it could break out of the loop and stop executing. For loops don’t have a natural way of stopping if a condition is met.

For loops are great for repetitive processes that occur a fixed number of times. If instead we have a repetitive process we keep repeating until a condition is met we instead need a while loop. This will automatically stop once the criteria is met. In our example, the game finishes when a player lands on square 100, so max(P) == 100, the game continues if the current player has not yet got to the final square so max(P) < 100.

For this programme to run we need to introduce some dice rolls. To simulate a dice, we sample from the numbers 1,2,3,4,5,6.

If you want to see this in code here is an example for R:

nPlayers <- 4

endSquare <- 100

snakes<-data.frame("Top" = c(14,28,34,68,85,96), "Bottom" = c(3,7,12,42,23,67))

ladders<-data.frame("Bottom" = c(5,22,38,51,64,72), "Top" = c(16,56,66,76,91,84))

# create vector of current positions

P<-rep(1, nPlayers)

# specify starting player

i<-1

while(max(P) < endSquare){

D <- sample(c(1:6),1)

P[i]<-P[i]+D

if( P[i] %in% snakes$Top){

P[i]<-snakes$Bottom[snakes$Top== P[i]]

print(paste("Player ", i, " goes down a snake."))

} else if (P[i] %in% ladders$Bottom) {

P[i]<-ladders$Top[ladders$Bottom == P[i]]

print(paste("Player ", i, " goes up a ladder."))

}

print(paste("Player", i, "is at square", P[i]))

if(i == nPlayers){

i <- 1

} else {

i <- i+1

}

}

A solution in python would be

import random

nPlayers = 4

endSquare = 100

snakes = { 14:3, 28:7, 34:12, 68:42, 85:23, 96:67 }

ladders = { 5:16 , 22:56 , 38:66 ,51:76 ,64:91 ,72:84 }

# create vector of current positions

P = [1]*4

# specify starting player

i = 0

while max(P) < endSquare:

D = random.randint(1,6)

print(D)

P[i] = P[i]+D

if P[i] in snakes:

P[i] = snakes[P[i]]

print("Player " + str(i + 1) + " goes down a snake.")

elif P[i] in ladders:

P[i] = ladders[P[i]]

print("Player " + str(i + 1) + " goes up a ladder.")

print("Player " + str(i + 1) + " is at square " + str(P[i]))

if i == (nPlayers - 1):

i = 0

else:

i+=1