Real computational tasks can be complicated. To accomplish them you need to THINK BEFORE YOU CODE.

Activity

In small groups discuss what you think the most important elements to think about before writing a program are. How do you approach the task?

What is an algorithm? What is a program?

An algorithm is a sequence of steps that solve a specific problem. A program is a sequence of instructions that tells the computer to do something. They differ from each other in that an algorithm will solve the problem while a program implements an algorithm in a form that a computer can execute. All computer programs are based on algorithms.

Although we might think of algorithms as complicated things used by programmers, in fact algorithms are used by people everyday to complete tasks. They range from incredibly simple to incredibly complex.

For example:

- The method of a carbonara recipe is an algorithm designed to assemble certain elements into a meal.

- Directions are an algorithm designed to navigate a person from A to B.

- How to read a clock.

- Wet laboratory protocol or or clinical trial protocol or data collection protocol

Algorithms are essential tools but they are also really powerful. Apart for the purpose of programming they can be advantageous for the following reasons

- Reproducibility - having a standardized process means you can ensure the same steps on every execution.

- Efficiency - knowing the stages of an algorithm means you can remove redundancy/identify repetitive processes.

- Scalability - a clearly defined process can easily be extended to run on larger datasets or more complex problems.

- Sharable - efficient way to share a process across colleagues, teams, departments or institutions.

- Automation - once a solution has be defined you can identify how it can be automated.

Faulty design vs faulty implementation

Being an efficient programmer is not only about writing code - it is about solving problems in a way that is translatable to a computer. It means using your knowledge of how a computer or language works, to use relevant constructs as the basis of your solution. Often what people think of as a problem with code writing is in fact a problem with the algorithm.

In many of the examples above (recipes and directions) we have probably experienced time when they go wrong. We can use these to demonstrate the distinction between errors in the algorithm compared to errors in how it is transcribed into instructions.

Let’s start with the case of directions, let’s say you’ve arrive in London at Paddington train station and you need to get to Edgware. A friend has helpfully written down the route by the Underground. Your algorithm is as follows:

- Get on the Hammersmith & City, Circle or District line.

- Ride one stop.

You follow these instructions and when you get off the tube, the sign at the station says Edgware Road. That’s not the right destination.

You call your friend. Their response is “Oh I thought you wanted to get to Edgware ROAD not Edgware”. This isn’t a problem with the instructions (i.e. the code) the problem is the algorithm had the wrong destination in mind when designing it. The instructions to get to the incorrect destination were correct and you followed them as planned.

Clear, on your required final destination, your friend now gives you some new directions. You write them down and follow them.

- Get on Hammersmith & City or Circle line

- Ride four stops to Kings Cross

- Change to Northbound Northern Line

- Ride to end of line.

Again you get out at your final destination, where the sign says High Barnet. The wrong location again! You call your friend, she runs through the instructions with you again and you compare to your written notes. This time you incorrectly wrote the instructions down. In this instance the problem was a coding error, the algorithm was fine, but you had an error in the set of instructions you used to navigate.

Typically coding errors are easier to detect and fix, than problems with the underlying algorithm. A good text editor with syntax and language highlight can prevent these. To pick up issues with the algorithm, requires more manual work, typically working through the algorithm and compare what the code is actually doing compared to what you thought it should be doing. This uses a combination of predicting and evaluation to debug your code.

Consider the exercise below:

Activity: Addition

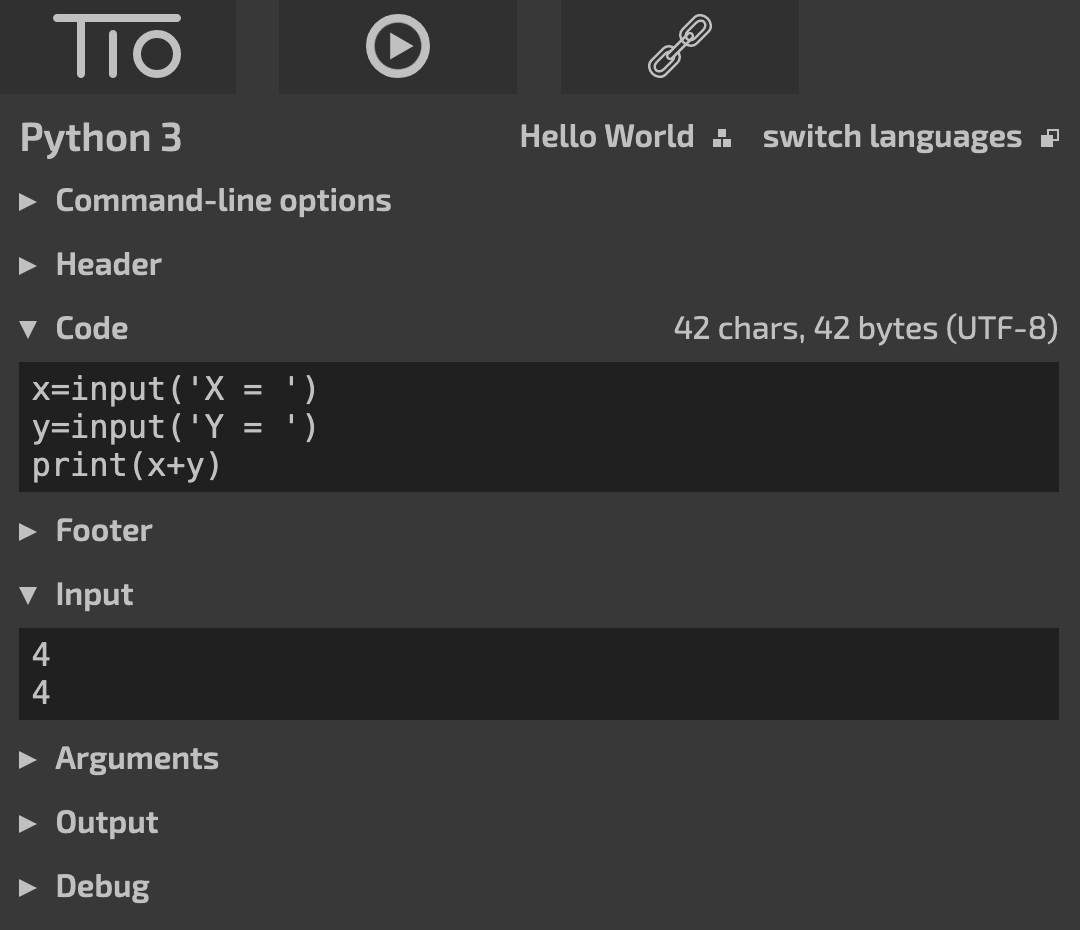

We have created a program that asks a user for x and y values and then returns the sum of them.

x=input('X = ')

y=input('Y = ')

print(x+y)

You can try this program using this online console: (https://tio.run/#python3)[https://tio.run/#python3]

Type the three lines of the program into the Code box.

Type your numeric input into the Input box as shown below:

Was the output as you expected?

Hmm… did we tell it what to do incorrectly? Or did we tell it to do the wrong thing?

To help decipher why it went wrong try setting ‘computational’ and ‘thinking’ as your input for X and Y. What is the difference between these types of input? Clue: type()

The problem here is that the code is not accepting the input as numeric values, it is treating them as text strings. Our algorithm is missing a critical step where is converts the text input into numeric values. The correct algorithm is coded below

x=input('X = ')

y=input('Y = ')

x = float(x)

y = float(y)

print(x+y)

Often what we think are issues with implementation are actually issues of algorithm. The claim there is something wrong with my code/script infers that the problem is syntax, when more likely the problem is with what you are asking the computer to do. This phrasing can be misleading as it fails to recognize the distinguish of the two possible sources of error.

Designing algorithms

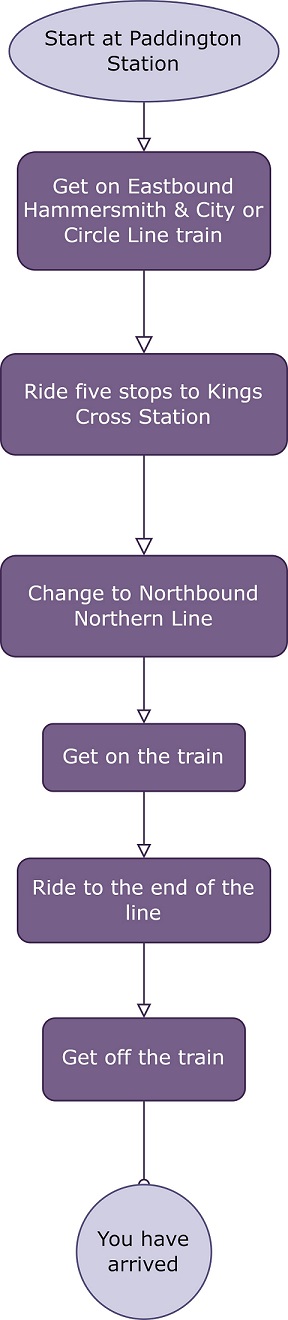

A simple way to represent an algorithm can be through a flowchart. This can be a useful tool for visualizing and designing the algorithm. The flowchart below represents the instructions to direct someone from Paddington Station to Edgware on the Underground.

This example is fairly straightforward as the steps are sequential and there is a single path through the network. You can think of this algorithm as a series of instructions.

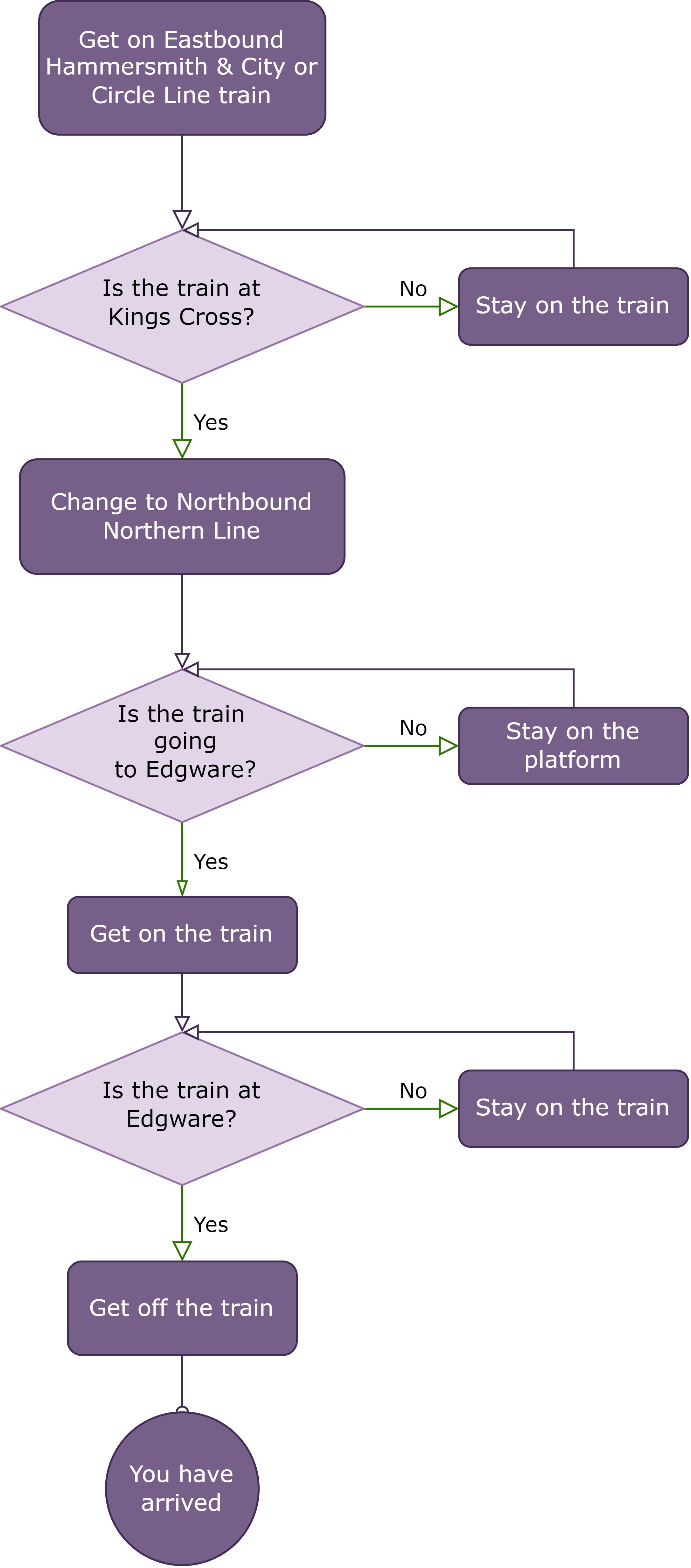

Alternatively the steps in the algorithm might need to be decisions or rules. In this instance we need to use logic or define conditional criteria which determine the pathway through the algorithm.

We can solve the same problem using a more complex flowchart that includes some decision making stages.

Most algorithms, especially complex ones, will need both components.

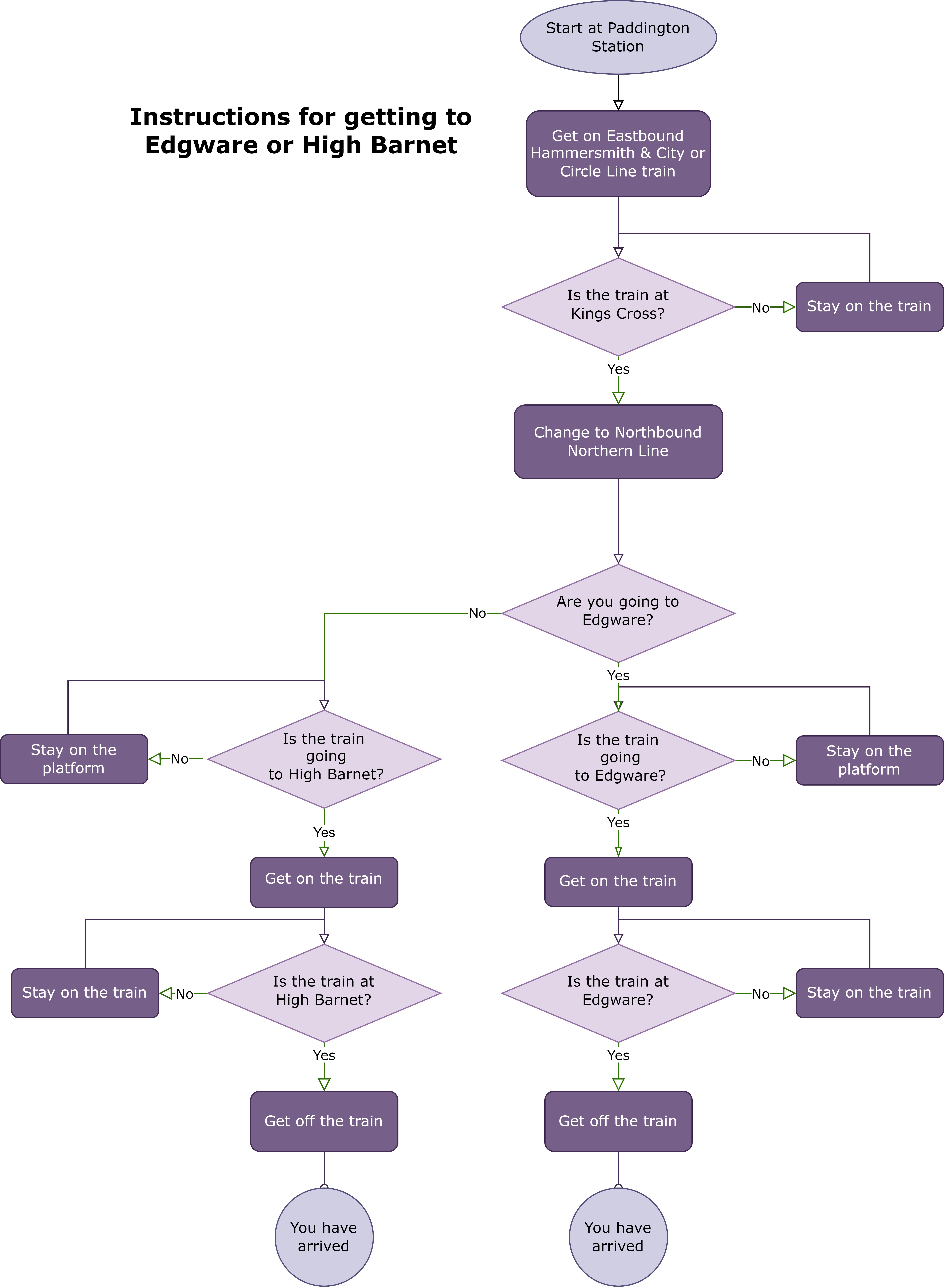

When you think about your algorithm as a series of steps, it become easy to see how you could extend it to solve more problems, or to make it more generalizable. For example, here is a single algorithm to navigate from Paddington to two different destinations.

Hopefully here you can appreciate, that the reason you can program multiple solutions to the same problem is because you can design multiple algorithms to solve the problem.

Activity: Snakes, ladders & flowcharts

Snakes and ladders is dice game where players advance along the board based on the roll of the dice. Upon landing on a square on the board, a player may either encounter a snake, where they are forced backwards a number of squares, a ladder, where they advance a number of squares, or nothing, in which case they remain on that square. A player wins when they reach the end of the board.

Design a flowchart for the game. The total number of board squares should be 100, and the maximum number of squares a player is advanced or returned should be 30.

If you want to create the flowchart online you can use this website (used to create the above flowchart). You will need to choose a location to save the output. We suggest OneDrive as this will link to your University OneDrive account.

When designing an algorithm there are techniques we can use to aid us in the design of the solution to our problem and design of our algorithm:

- decomposition

- pattern recognition

- abstraction

You may have implemented some of these already, knowingly or unknowingly, in the previous activity. We are going to cover each of these in the following sections.